This is a terrific review of the Ram reissue. Often I can’t stand the show-offy braininess of Pitchfork’s writers, but here Jayson Greene just hits too many bulls eyes for me to quibble about it.

Ram, simply put, is the first Paul McCartney release completely devoid of John’s musical influence. Of course, John wiggled his way into some of the album’s lyrics– in those fresh, post-breakup years, the two couldn’t quite keep each other out of their music. But musically, Ram proposes an alternate universe where young Paul skipped church the morning of July 6, 1957, and the two never crossed paths. It’s breezy, abstracted, completely hallucinogen-free, and utterly lacking grandiose ambitions. Its an album whistled to itself. It’s purely Paul.

Greene pokes around the issue of how hated the record was on release, expressed from on high by Rolling Stone’s Jon Landau: “the nadir in the decomposition of Sixties rock thus far.” (Now that there is an insufferably pretentious rock critic).

Greene sees some sort of family dynamic in Landau’s (and generally speaking sixties hipster elite) opinion:

Landau was right, however, that [it] did spell the end of something, which might be a clue to the vitriol: If “60s rock” was defined, in large part, by the existence of the Beatles, then Ram made it clear in a new, and newly painful, way that there would be no Beatles ever again. To use a messy-divorce metaphor: When your parents are still screaming red-faced at each other, it’s a nightmare, but you can still be assured they care. When one of them picks up and continues on living, it smarts in an entirely different way.

I want to run with that messy divorce thing for a moment longer. When talking about the Beatles it seems necessary to state one’s Team John or Team Paul bias. I have always leaned Team Paul.

I was once commissioned to write a book for young teens about the McCartney family. (Still in print! and screaming up the Amazon Best Sellers list: now cresting at #2,727,671!!!).

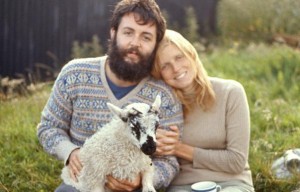

Specifically it was “Famous Families,” Paul and Stella, but you can’t write about that family without getting sucked into the pastoral idyll to which Paul retreated immediately after the Beatles crashed and burned. It enraged many, apparently, but looking at it today, I just wonder: “Who could possibly have a problem with this?”

Anyway, I’m definitely Team Paul, but yeah, as a product of the broken home that is the Beatles marriage, do want to shout, “I love dad too, and I just wish you two would stop fighting.” And start to cry, retreat to my room, and slam the door. Or I would, if they hadn’t actually divorced four decades ago.

Also, interesting stuff about the City and the Country:

“I want a horse, I want a sheep/ Want to get me a good night’s sleep,” Paul jauntily sings on “Heart of the Country”, a city boy’s vision of the country if ever there was one, and another clue to the record’s mindstate. For Paul, the country isn’t just a place where crops grow; it’s “a place where holy people grow.” Now that American cities everywhere are having their Great Pastoral Moment, full of artisans churning goat’s-milk yogurt and canning their own jams, Ram feels like particularly ripe fruit.

A lot to answer for, from one perspective, but you know, always ahead of his time, that Macca.

I can’t help thinking about the Ram period without also thinking about Ronnie Lane’s parallel retreat from rock stardom. It didn’t come out near as well for Ronnie, who of course was not quite in Paul’s league musically, and didn’t end up one of Britain’s wealthiest men (he was absolutely an idiot with money–kept his rock star dough in a plastic bag in his house), and had the bad fortune to come down with a crippling degenerative fatal disease.

But the rootsy, rustic, slightly clueless back-to-the-country vibe is the same, and a beautiful thing, too. I don’t know what is going on with the famous Beatles Spotify holdout, as I am able to post a Ram reissue playlist. Maybe that’s temporary. Sadly, there remains a massive hole in Spotify’s catalog where Ronnie Lane’s music should go.