Simon Owens’ Clash of the Blogosphere Titans sees Glenn Greenwald’s relentless (and entirely justified) criticism of Atlantic correspondent Jeffrey Goldberg as a useful yardstick with which to measure “the effect of media criticism in a Web 2.0/3.0 age.”

The journalistic catastrophes that made Goldberg’s name synonymous with spectacular wrongheadedness, a pair of long pieces about the Iraq threat for the New Yorker (the first one titled “The Great Terror”), came back in 2002.

Times have changed. Today, Greenwald, a “blogger” (a term of utter contempt once, now losing its bite) has a featured column at Salon, a site that gets far more online readership than the Atlantic, according to Owens, as well as a New York Times bestseller to his credit. Owens says Greenwald now possesses the clout to compel Goldberg to respond to criticism, especially as regards “The Point of No Return,” his attempt to replicate his scare/war-mongering success, this time with regard to Iran.

Goldberg declined Owens’ invitation to discuss his disputes with Greenwald; Greenwald did not. Responding to the suggestion that his singular focus on Goldberg might be perceived as an “obsessive feud,” Greenwald tells Owens that Goldberg’s stature demands close scrutiny:

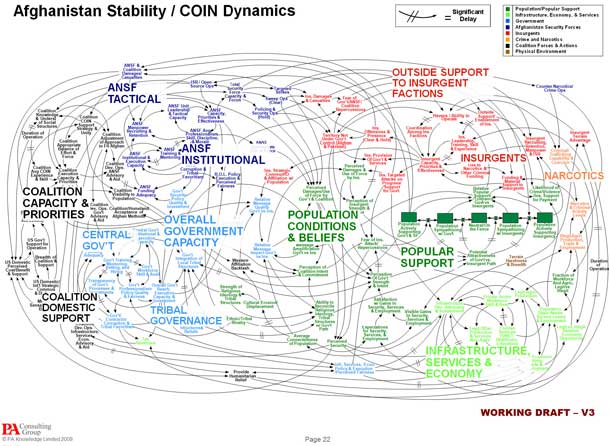

“[T]here are two things that distinguish this case. One is the consequentiality of it and the centrality [Goldberg] played. It wasn’t like he was just kind of wrong about something, he was one of the leading people validating the war. The thing that happened in the Iraq War is that obviously the right got behind it because the people on the right — the leaders on the right — were clearly behind it. But in order to make it a majoritarian movement, they had to get centrists and liberals behind it. So they needed liberal validators … There’s probably nobody that you can compare in influence to getting Democrats and liberals to support the war than Jeffrey Goldberg. It wasn’t just that he was for the war, he was using his status as a reporter to feed lies. I mean he didn’t just write one New Yorker piece but a second one too, and he was all over the television with this stuff saying that Saddam had a very active nuclear program and most importantly that Saddam had an enthusiastic alliance with al-Qaeda.”

The second distinguishing characteristic of Goldberg, Greenwald argued, is that he’s one of the few mainstream reporters who hasn’t issued a mea culpa on the facts he got wrong. Greenwald pointed out that though Judith Miller paid a career price for her Iraq reporting at the New York Times, Goldberg — who Greenwald considers equally culpable — continues to gain prominence despite doubling down on his past reporting. In fact, Goldberg recently used his blog to argue that there truly was a strong connection between Saddam and al-Qaeda.

It’s true that Goldberg has responded to Greenwald multiple times over the Iran piece, both on his blog and as a guest on NPR, but these responses have been perfunctory at best, mendacious at worst:

“It’s almost like his responses are three or four years behind. When I first started writing about criticizing media figures — establishment media figures — that was very much the reaction. It was a very lame sort of not-really-attentive response, just dismissive or plain mockery. Like, ‘I don’t have to respond because in my world he’s nobody and I’m somebody so the most I’m going to do is be derisive about this.’ That’s a journalist/blogger cliché from 2005, and most journalists know they can no longer get away with it. He’s living in a world where he thinks it doesn’t affect his reputation. Among his friends it doesn’t. I’m sure he calls [TIME writer] Joe Klein or whoever else I’ve criticized and he’s like ‘he’s an asshole and a prick, don’t worry about that.’ But I guarantee you that there are a lot more people reading the stuff I write than the stuff he writes, in terms of sheer number. And the level of impact that that kind of level of critique has is infinitely greater than it was three years ago. So I’m sure he tells himself and convinces himself that it doesn’t actually matter but it does. And it’s hurting his credibility.

True, but my more cynical take is that Goldberg’s credibility is not the point. Or at least it isn’t anymore. In fact, his willingness to use his credentials as a correspondent for the New Yorker (liberal! fastidiously fact-checky!) to stretch the case for war with Iraq, at the cost of his journalistic reputation in the “reality-based community,” was what got him to the pinnacle of the blogging profession.

This sort of failing upwards is not a new thing, especially given Goldberg’s journalistic focus.

If you make a case for a militaristic solution to a perceived problem, and possess even a middling capacity for persuasion, and if you make that case boldly and loudly enough, you are well on your way a successful career in punditry in America.

Why should Goldberg apologize? Reckless accusations that lead to war, in the face of contrary facts and likely catastrophic consequences, are a feature, not a bug.