Happy is the wrong word, but I find it gratifying to see that Tony Blair is being raked over the coals by his own government for his role in the monstrous, illegal by any possible definition, attack and occupation of Iraq.

The Guardian has a great deal of good coverage on the Chilcot panel here, including live streaming video. Here in the States, a clever Gawker commenter noted that Blair’s demeanor could be summed up thusly: “1/3 happy to explain to you dolts, 1/3 pained that he wasn’t being understood and 1/3 “SHIT! Busted’.”

Independent columnist Matthew Norman writes that following this inquiry Blair will remain a free man, and that this is regrettable, especially since he will continue to earn up to the neighborhood of half a million dollars a day giving speeches. But Norman finds some solace in the fact that Blair will never be completely at ease:

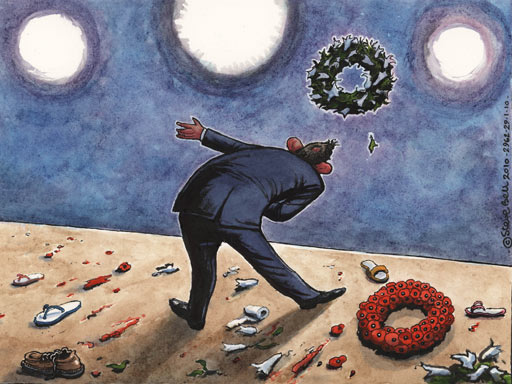

For Mr Blair, the journey will not end on Friday, or when the inquiry publishes its findings. However damning these appear, however transparent the intent to cast him as a deceitful warmonger, they will be written in the language of euphemism, thus allowing each side to claim a victory of sorts. For Mr Blair, in fact, the trek can never end. Even if he is as canny in his choice of foreign destinations as he is with his answers on Friday, and avoids any Pinochet-type indignity, much less a war crimes trial, he … must trudge through his remaining days as a pariah.

This, it seems to me, is justice. It isn’t a modern form of quick-fix justice, as would be evidenced by front-page pictures of him being led into a Dutch courthouse, and then led out of it to a cell. Erich Segal, who moonlighted as a professor of classics, might confirm that this is justice ancient Greece style, in which the offence of Olympian arrogance – of confusing one’s puny self with a deity – was punished by something even more agonising than global humiliation or a lengthy spell in jug. The penalty from which death alone can free Mr Blair is soul-crushing futility. For the rest of his life, he must push the boulder of his self-proclaimed innocence and self-protested good intent up the hill, aware that he cannot reach the summit but powerless to evade the pointlessness of trying.

…For all the braggadocio, the sunken eyes and haunted expression betray his fear of arrest, and even more so his awareness of the loathing felt for him here and around the world. He may or may not be tortured on Friday by the Furies, as represented by the parents of troops killed in Iraq, but he will be tormented until the only Judgment Day he tells us means anything to a demigod whose stature far transcends the insolent judgments of mankind. If he leaves for a well-guarded gated community in the United States or Australia, he will be an exile. If he stays to flit between his many homes in England, he will be an outcast in his own land. Robert Harris brilliantly portrayed him as The Ghost in his excellent novel of that name. Now he looks more like one of The Undead.

That’s nice, but for some, it’s not enough. Guardian columnist George Monbiot has set up an Arrest Blair web site, which “offers a reward to people attempting a peaceful citizen’s arrest of the former British prime minister, Tony Blair, for crimes against peace. Anyone attempting an arrest which meets the rules laid down here will be entitled to one quarter of the money collected at the time of his or her application.” As of this morning, Friday Jan. 29, the kitty is closing in on ten thousand quid. Monbiot has a history with this sort of thing, having attempted a citizen’s arrest on John “Bonkers” Bolton at the Hay festival in 2008. By Monbiot’s own description, this was a “feeble attempt” to bring Bolton to justice. And yet, I like the thinking behind it. Let’s hope it spreads across the Atlantic.